cawacko

Well-known member

Goof read from John Mauldin's weekly column, this on inflation. For the TL,DR crowd he says it's better than it was and higher than it should be. He drills down into certain measures of how we judge inflation (housing is measured but the cost of cars and insurance, which is way up, doesn't fully show up in the data).

It speaks to why there is so much pessimism towards the economy even with certain data figures looking good. (He also shows some historical polling and trending about people in this country becoming less optimistic overall.)

(This is not the entire column, it's too many words to post. He speaks to politics and what inflation will likely look like under a post election Biden or Trump Presidency which I could not include.)

Today, for example, I will again say something I observed just two weeks ago: Inflation is both better than it was and higher than it should be. You must recognize those two points to know where the economy is and where it’s going.

Another thing I often note is that inflation is individualized. Everyone experiences it differently based on their situation. But one thing is consistent. As time passes, the “better than it was” aspect fades while the “higher than it should be” part takes over.

We see this in public opinion and consumer sentiment surveys. Paul Krugman, Jared Bernstein, and so many others wonder why people don’t feel better than the polls and surveys suggest. They have a point. Unemployment is close to an all-time low, wages are rising, GDP is still growing modestly, inflation is falling, the stock market is pushing all-time highs and continues to make even new and higher highs, you can get 5% on your money market accounts, and so on.

All that notwithstanding, millions say their situations are getting worse and they aren’t happy about it. Moreover, they aren’t wrong. I’ve talked before (see, I’m doing it again) about inflation having a cumulative effect. Prices may be rising more slowly, but they’re still higher than they were and certainly not falling. That hurts even if inflation is “only” 2%.

Data is important but not everything. Perceptions matter, too. Today we’ll look at how people feel inflation and what it may mean in the years to come.

But first, and really quick, I want to thank the hundreds of people who sent in title suggestions for my new book. I literally sorted through multiple hundreds of potential titles and have narrowed it down to 5 titles and 5 subtitles. You can click on this link and take a 20-second survey on which title and subtitle you like.

Don't think about it too much—just which one or two resonates with you. Then do the same for the subtitles. After that, there will be a section where you can send any comments. I will read every one of them. Thanks in advance.

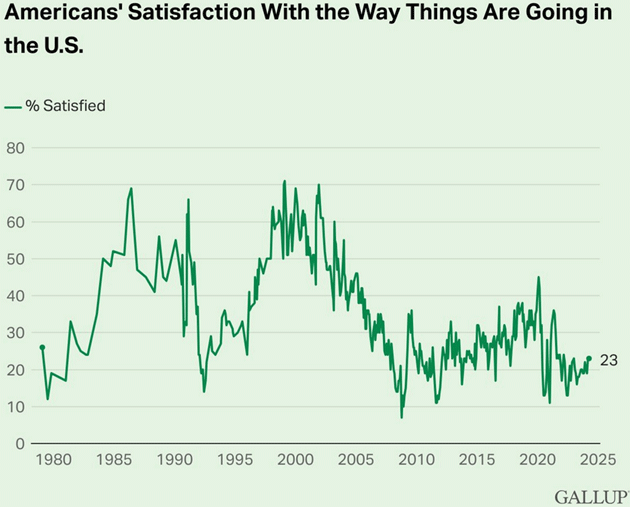

According to Gallup, Americans have been generally grumpy for two decades now. Their regular monthly survey series shows public satisfaction with “the way things are going” was over 70% at the turn of the Millennium, then dropped below 50% in 2004 and is now down another 20 points to only 23%. Ugh.

The way this series evolves is instructive. Public satisfaction was also quite low when the data begins in 1980—also a period of high inflation. But feelings improved throughout that decade, then fell again in the early 1990s. That was a recessionary period and is one reason George H.W. Bush lost to Bill Clinton in 1992. Then it fell a third time in the early 2000s, leading to the 2008 recession.

But that time, it didn’t recover much. A majority of Gallup respondents have been dissatisfied in every survey since 2004. Why? What has kept us continuously net-pessimistic for 20 years now? I don’t know. But whatever it was seems to have preceded the more recent political divisions—and may have helped cause those divisions.

This is important to understanding inflation perceptions. Many who are now upset about inflation (with good reason, as we’ll see below) were already upset long before inflation became a problem.

We should also note inflation, while not a new phenomenon, is a new experience for most people. They simply haven’t lived as adults through anything like 2021‒2023 or, if they have, only saw it decades ago.

This chart shows CPI’s annual rate by month for the last 25 years. I drew a red line at the 3% level.

Just for fun, let’s look at inflation since WW2. There is clearly some correlation between the mood of the country (Gallup poll above) and inflation. It’s not perfect, of course, but inflation is clearly important.

If, for most of your life, you hear “inflation” described mostly as something that never happens anymore, and then it suddenly starts happening, of course you are upset. You face a new and troublesome problem that’s not your fault and is largely uncontrollable. You thought it would never hurt you. Yet it is.

My eight children are a readily accessible panel of young adults. They have all built independent lives of which I’m quite proud, but they share many of their generations’ problems, too. When I reached out to ask how inflation is affecting them, they almost blew up my phone with long, impassioned text messages.

Some background: I have two biological daughters and adopted five children. My wife Shane added another young man. Their ages range from 25 to 47. All told, I'm a father to two black sons, two Asian daughters, a blonde, brunette, redhead and a card-carrying Choctaw Indian. Nine grandkids with more shots on goal coming. Only one is 100% Caucasian. The rest have some hyphen in their ethnicity. Four graduated college. Two are STILL(!) working at it. Three have serious life-threatening health issues. All are working and decidedly middle class, although some would argue they only wish they were middle class. They don’t feel middle class.

I think they are a good proxy for cross-culture America. With the caveat these are anecdotes, not data, I’ll share some of their (slightly edited) thoughts below. I suspect you would get similar responses from your own family networks.

As you might expect, housing prices were high on the headache list. This is the single biggest expense for most households and my kids are no exception.

Amanda: “A starter home (3 BR/2 BA) in Tulsa back in 2014 when we bought ours was $97,000 with a 3% mortgage rate. Now the same kind of homes are $265,000 with 5‒8% mortgages.” (Note: This would represent a 173% price increase in 10 years, plus the higher mortgage rate now.)

Tiffani: “To lease a house in Frisco (Dallas area), they wanted a two-year lease with a 5% increase after year one. I negotiated and it’s now a two-year lease with a 5% increase on renewal. Plus utilities… two years ago I could get electric service for about 10 cents/kwh. Now the lowest I can find is 15‒16 cents.”

(For those in other states, parts of Texas have a competitive system where you can choose your electric provider. Though in this case, it seems the competition isn’t exactly bringing prices down.)

Melissa: “Average rent for a 1-bedroom in Austin is $1,642. It was $1,200 in 2020. And to qualify to rent an apartment you have to make three times rent so to qualify to rent a one-bedroom in Austin right now you have to make almost $30 an hour.”

Trey has been hunting for a place for several months. He is now renting a house for $2,000 in an almost country suburb of Dallas and will add some roommates to bring costs down. Chad just downsized even with a new kid. Dakota is living in a nice mobile van with his SO to keep costs down as he goes to welding school. Abigail tells her siblings to check out Habitat for Humanity, talking about lower costs and subsidized interest rates.

www.mauldineconomics.com

www.mauldineconomics.com

It speaks to why there is so much pessimism towards the economy even with certain data figures looking good. (He also shows some historical polling and trending about people in this country becoming less optimistic overall.)

(This is not the entire column, it's too many words to post. He speaks to politics and what inflation will likely look like under a post election Biden or Trump Presidency which I could not include.)

Inflationary Perceptions

Today, for example, I will again say something I observed just two weeks ago: Inflation is both better than it was and higher than it should be. You must recognize those two points to know where the economy is and where it’s going.

Another thing I often note is that inflation is individualized. Everyone experiences it differently based on their situation. But one thing is consistent. As time passes, the “better than it was” aspect fades while the “higher than it should be” part takes over.

We see this in public opinion and consumer sentiment surveys. Paul Krugman, Jared Bernstein, and so many others wonder why people don’t feel better than the polls and surveys suggest. They have a point. Unemployment is close to an all-time low, wages are rising, GDP is still growing modestly, inflation is falling, the stock market is pushing all-time highs and continues to make even new and higher highs, you can get 5% on your money market accounts, and so on.

All that notwithstanding, millions say their situations are getting worse and they aren’t happy about it. Moreover, they aren’t wrong. I’ve talked before (see, I’m doing it again) about inflation having a cumulative effect. Prices may be rising more slowly, but they’re still higher than they were and certainly not falling. That hurts even if inflation is “only” 2%.

Data is important but not everything. Perceptions matter, too. Today we’ll look at how people feel inflation and what it may mean in the years to come.

But first, and really quick, I want to thank the hundreds of people who sent in title suggestions for my new book. I literally sorted through multiple hundreds of potential titles and have narrowed it down to 5 titles and 5 subtitles. You can click on this link and take a 20-second survey on which title and subtitle you like.

Don't think about it too much—just which one or two resonates with you. Then do the same for the subtitles. After that, there will be a section where you can send any comments. I will read every one of them. Thanks in advance.

Can’t Get No Satisfaction

Inflation isn’t perceived in a vacuum. It is one of many conditions that combine into a general sense of happiness, or lack thereof. We have to consider the entire milieu.According to Gallup, Americans have been generally grumpy for two decades now. Their regular monthly survey series shows public satisfaction with “the way things are going” was over 70% at the turn of the Millennium, then dropped below 50% in 2004 and is now down another 20 points to only 23%. Ugh.

The way this series evolves is instructive. Public satisfaction was also quite low when the data begins in 1980—also a period of high inflation. But feelings improved throughout that decade, then fell again in the early 1990s. That was a recessionary period and is one reason George H.W. Bush lost to Bill Clinton in 1992. Then it fell a third time in the early 2000s, leading to the 2008 recession.

But that time, it didn’t recover much. A majority of Gallup respondents have been dissatisfied in every survey since 2004. Why? What has kept us continuously net-pessimistic for 20 years now? I don’t know. But whatever it was seems to have preceded the more recent political divisions—and may have helped cause those divisions.

This is important to understanding inflation perceptions. Many who are now upset about inflation (with good reason, as we’ll see below) were already upset long before inflation became a problem.

We should also note inflation, while not a new phenomenon, is a new experience for most people. They simply haven’t lived as adults through anything like 2021‒2023 or, if they have, only saw it decades ago.

This chart shows CPI’s annual rate by month for the last 25 years. I drew a red line at the 3% level.

Notice how inflation stayed below 3% for long stretches in the early 2000s. Then, other than 2011, it was below 3% and at times near 0% from late 2008 until the COVID recovery began in 2021. Now the former 3% ceiling looks more like the floor.Just for fun, let’s look at inflation since WW2. There is clearly some correlation between the mood of the country (Gallup poll above) and inflation. It’s not perfect, of course, but inflation is clearly important.

Compared to anything seen in the adult lives of today’s consumers under 65, three straight years of 3% or higher inflation is simply unprecedented. It is remarkably worse than anything they remember. In fact, what they remember is often falling prices for many products, since this was also the period when low-priced Chinese goods were flooding into US stores, as well as high productivity which meant lower prices. I have written letters on the “bad” kind of deflation. But…If, for most of your life, you hear “inflation” described mostly as something that never happens anymore, and then it suddenly starts happening, of course you are upset. You face a new and troublesome problem that’s not your fault and is largely uncontrollable. You thought it would never hurt you. Yet it is.

Headache List

The Federal Reserve’s annual household survey, just released but conducted last October, found 65% of US adults said rising prices had made their financial situations worse, including 19% who said it made their situations much worse. I haven’t seen crosstabs, but I feel sure this group skews young.My eight children are a readily accessible panel of young adults. They have all built independent lives of which I’m quite proud, but they share many of their generations’ problems, too. When I reached out to ask how inflation is affecting them, they almost blew up my phone with long, impassioned text messages.

Some background: I have two biological daughters and adopted five children. My wife Shane added another young man. Their ages range from 25 to 47. All told, I'm a father to two black sons, two Asian daughters, a blonde, brunette, redhead and a card-carrying Choctaw Indian. Nine grandkids with more shots on goal coming. Only one is 100% Caucasian. The rest have some hyphen in their ethnicity. Four graduated college. Two are STILL(!) working at it. Three have serious life-threatening health issues. All are working and decidedly middle class, although some would argue they only wish they were middle class. They don’t feel middle class.

I think they are a good proxy for cross-culture America. With the caveat these are anecdotes, not data, I’ll share some of their (slightly edited) thoughts below. I suspect you would get similar responses from your own family networks.

As you might expect, housing prices were high on the headache list. This is the single biggest expense for most households and my kids are no exception.

Amanda: “A starter home (3 BR/2 BA) in Tulsa back in 2014 when we bought ours was $97,000 with a 3% mortgage rate. Now the same kind of homes are $265,000 with 5‒8% mortgages.” (Note: This would represent a 173% price increase in 10 years, plus the higher mortgage rate now.)

Tiffani: “To lease a house in Frisco (Dallas area), they wanted a two-year lease with a 5% increase after year one. I negotiated and it’s now a two-year lease with a 5% increase on renewal. Plus utilities… two years ago I could get electric service for about 10 cents/kwh. Now the lowest I can find is 15‒16 cents.”

(For those in other states, parts of Texas have a competitive system where you can choose your electric provider. Though in this case, it seems the competition isn’t exactly bringing prices down.)

Melissa: “Average rent for a 1-bedroom in Austin is $1,642. It was $1,200 in 2020. And to qualify to rent an apartment you have to make three times rent so to qualify to rent a one-bedroom in Austin right now you have to make almost $30 an hour.”

Trey has been hunting for a place for several months. He is now renting a house for $2,000 in an almost country suburb of Dallas and will add some roommates to bring costs down. Chad just downsized even with a new kid. Dakota is living in a nice mobile van with his SO to keep costs down as he goes to welding school. Abigail tells her siblings to check out Habitat for Humanity, talking about lower costs and subsidized interest rates.

|

Inflationary Perceptions

Inflation data is important but perceptions matter, too. John Mauldin looks at how people feel inflation and what it may mean in the years to come.