AProudLefty

Adorable how loser is screeching for attention. :)

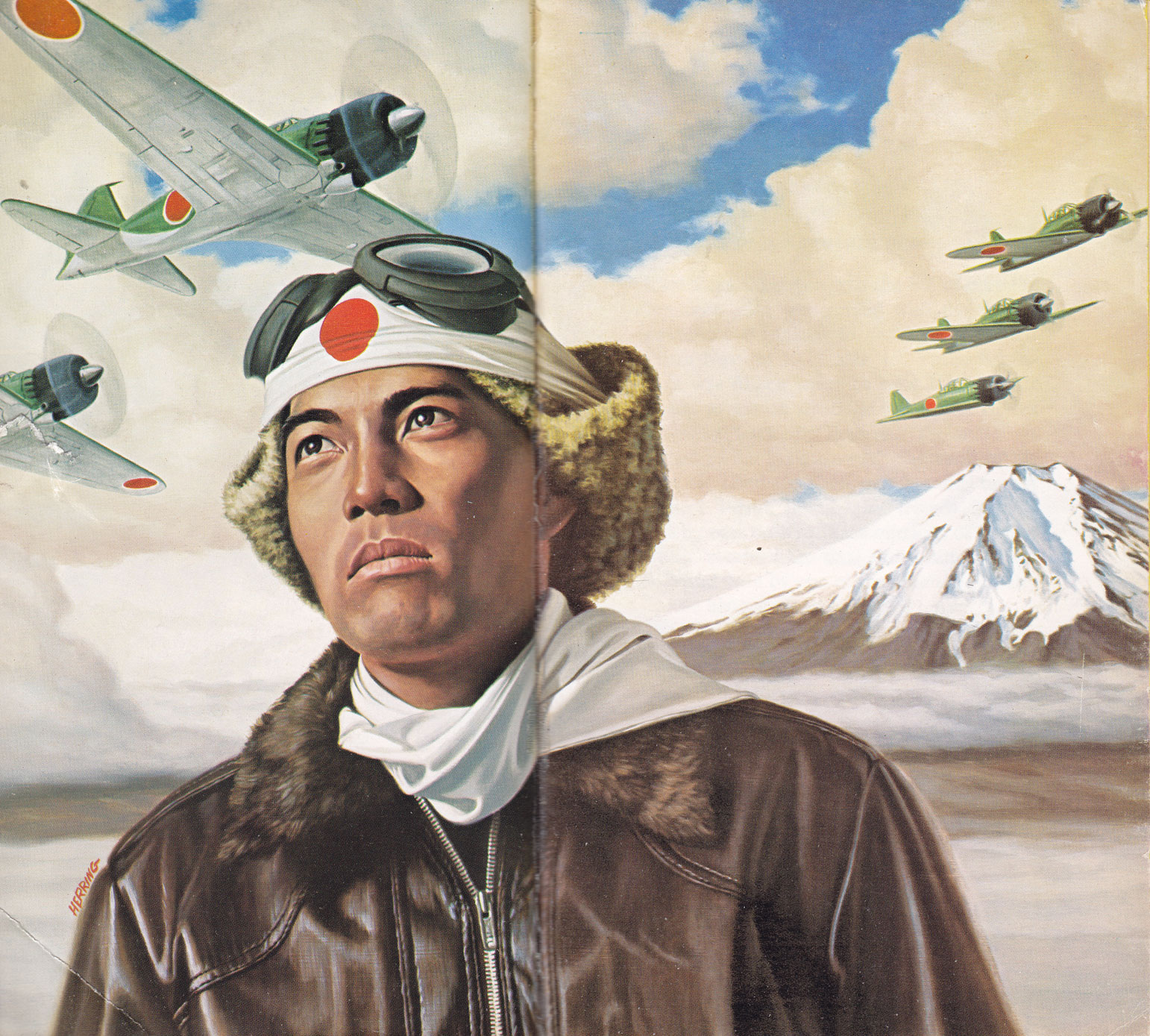

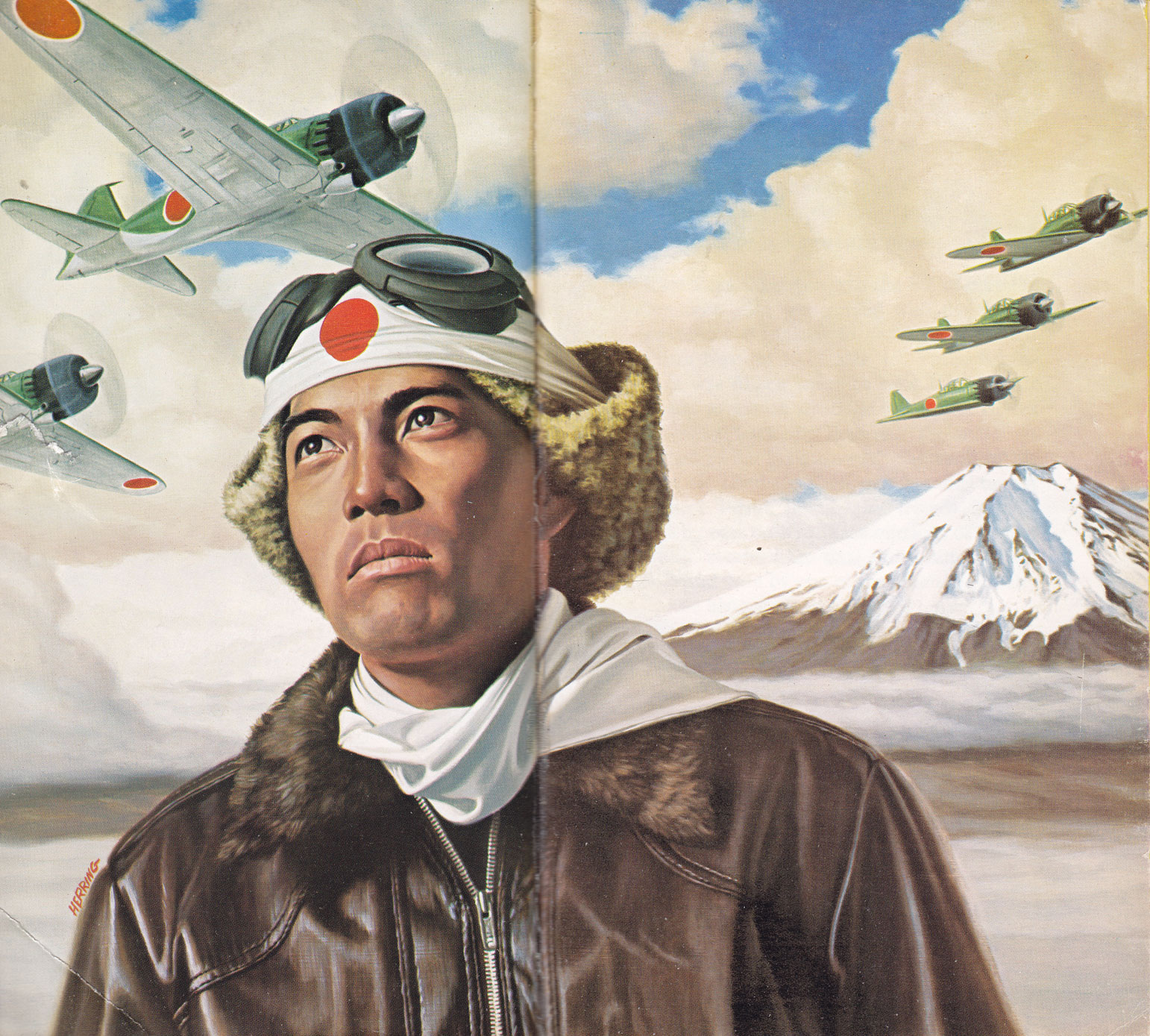

I know it is not December yet but I was in the mood to watch "Pearl Harbor" so I thought I'd share.

A few years ago, when I was making a BBC TV documentary series about the Japanese and World War II, I mentioned to a colleague that I was leaving for Tokyo in order to meet a kamikaze pilot. “Are you crazy?” he said. “How can you meet a kamikaze pilot? These guys all killed themselves in suicide attacks on Allied ships! They disintegrated into a million pieces 60 years ago!”

He was wrong. Unlikely as it may seem, a number of Japanese kamikaze pilots did survive the war. All had been instructed to return to base if their planes developed a fault on the way to their targets. That is how I came to meet Kenichiro Oonuki. Back in April 1945 he had been forced to land his plane—stuffed with explosives—because of engine trouble while he was en route to attack the American fleet off Okinawa. He was rescued by the Japanese navy and interrogated about the reasons for the failure of his mission. Meanwhile, the war in the Pacific ended.

He told me that his survival had given him “a sense of a burden.” He knew he wasn’t supposed to be talking to me 60 years after the end of the war—that he should have, as my colleague had said, smashed his plane into the superstructure of an American warship. But the fact that he did survive meant that he was able to correct the central myth of the kamikaze—that these young pilots all went to their deaths willingly, enthused by the Samurai spirit.

On the contrary, Oonuki said, when he and his fighter pilot colleagues were first asked to volunteer for this “special attack mission” they thought the whole idea “ridiculous.” But, given the night to think about their decision, the men reconsidered. They feared that if they did not volunteer, their families would be ostracized and their parents told that their son was “a coward, not honorable, shameful.”

My friend in Japan and I talked about this. He said that indeed it's better to die than to have dishonor on one's family.

Now he warns that in a time of crisis, like the Second World War, “you are drawn into this major vortex and swirl around without your own will.”

Sounds familiar?

Before I met Kenichiro Oonuki I thought the Japanese kamikaze pilots must have been—literally—deranged. But I emerged, having listened to his calm, measured explanation, thinking something much more terrifying—the kamikaze were quite, quite sane.

Yep. Sane people have been caught in wars that they have no control over.

God bless the soldiers, no matter who they are.

Clint Eastwood's "Letters From Iwo Jima" is an awesome movie.

A few years ago, when I was making a BBC TV documentary series about the Japanese and World War II, I mentioned to a colleague that I was leaving for Tokyo in order to meet a kamikaze pilot. “Are you crazy?” he said. “How can you meet a kamikaze pilot? These guys all killed themselves in suicide attacks on Allied ships! They disintegrated into a million pieces 60 years ago!”

He was wrong. Unlikely as it may seem, a number of Japanese kamikaze pilots did survive the war. All had been instructed to return to base if their planes developed a fault on the way to their targets. That is how I came to meet Kenichiro Oonuki. Back in April 1945 he had been forced to land his plane—stuffed with explosives—because of engine trouble while he was en route to attack the American fleet off Okinawa. He was rescued by the Japanese navy and interrogated about the reasons for the failure of his mission. Meanwhile, the war in the Pacific ended.

He told me that his survival had given him “a sense of a burden.” He knew he wasn’t supposed to be talking to me 60 years after the end of the war—that he should have, as my colleague had said, smashed his plane into the superstructure of an American warship. But the fact that he did survive meant that he was able to correct the central myth of the kamikaze—that these young pilots all went to their deaths willingly, enthused by the Samurai spirit.

On the contrary, Oonuki said, when he and his fighter pilot colleagues were first asked to volunteer for this “special attack mission” they thought the whole idea “ridiculous.” But, given the night to think about their decision, the men reconsidered. They feared that if they did not volunteer, their families would be ostracized and their parents told that their son was “a coward, not honorable, shameful.”

My friend in Japan and I talked about this. He said that indeed it's better to die than to have dishonor on one's family.

Now he warns that in a time of crisis, like the Second World War, “you are drawn into this major vortex and swirl around without your own will.”

Sounds familiar?

Before I met Kenichiro Oonuki I thought the Japanese kamikaze pilots must have been—literally—deranged. But I emerged, having listened to his calm, measured explanation, thinking something much more terrifying—the kamikaze were quite, quite sane.

Yep. Sane people have been caught in wars that they have no control over.

God bless the soldiers, no matter who they are.

Clint Eastwood's "Letters From Iwo Jima" is an awesome movie.