A little history every side should wanna review..

Democrats debating whether to impeach Donald Trump may be misreading the evidence from the last time the House tried to remove a president.

It’s become conventional wisdom—not only among Democrats but also among many political analysts—that House Republicans paid a severe electoral price for moving against Bill Clinton in 1998, at a time when polls showed most of the public opposed that action.

But that straightforward conclusion oversimplifies impeachment’s effects, according to my analysis of the election results and interviews with key strategists who were working in national politics at the time. While Republicans did lose House seats in both 1998 and 2000, Democrats did not gain enough to capture control of the chamber either time. And in 2000, lingering unease about Clinton’s behavior provided a crucial backdrop for George W. Bush’s winning presidential campaign—particularly his defining promise “to restore honor and dignity” to the Oval Office.

Matthew Dowd, a senior strategist for Bush’s 2000 campaign, told me that Democrats today “are learning the wrong lessons” from Clinton’s impeachment by neglecting to consider how it shaped both election cycles, especially the presidential race. In January 2001, almost exactly two years after House Republicans defied public opinion to impeach Clinton, the GOP controlled the White House, the House, and initially the Senate. (Within months, the Republican Jim Jeffords of Vermont would switch parties, shifting control to the Democrats.) “Having gone through all that,” Dowd said, “I think the Democrats are way too skittish on impeachment.”

Tad Devine, a senior strategist for Al Gore, the Democratic nominee in 2000, concurs. Bush’s ability to tap the public’s dismay over Clinton’s personal life “more than anything else got in our way in terms of winning the election,” he told me. Even if the Senate doesn’t convict Trump, Devine believes, impeachment in the House could offer Democrats a similar chance to highlight the aspects of Trump’s volatile behavior that most alienate swing voters.

But it’s easy to overstate the magnitude of the GOP’s backslide in 1998. In the Senate, Democrats gained no seats that year, leaving the Republican majority intact. Nor did the five-seat House loss cost the GOP its majority in that chamber. Republicans still won more of the total national popular vote in House races than Democrats. Swing voters didn’t stampede away from the GOP; in exit polls, Republicans still narrowly beat Democrats among independent voters. And while impeachment provoked big turnout from African Americans, Clinton’s most passionate supporters, overall, turnout that year was very low.

The midterm election was widely seen as a red light from the public on impeachment. But Republicans barreled ahead and voted in mid-December to remove Clinton anyway. On the day they did so, there was about as much public support for impeaching Clinton as there is today for impeaching Trump. A Gallup poll at the time showed that 35 percent of the public overall backed impeachment, including 40 percent of independents. In a CNN poll this week, 41 percent of the public supported impeachment, including 35 percent of independents. Overall, Clinton’s public support in Gallup polling was much stronger at the time (63 percent job-approval rating) than Trump’s is now (40 percent).

After the Senate refused to remove him in early 1999, Clinton’s job approval remained about a buoyant 60 percent through the rest of his presidency. But that strong number coexisted with substantial public disapproval of the personal behavior that the Starr investigation and the impeachment inquiry had highlighted.

Those personal doubts about the outgoing president cast a huge shadow over the election to succeed him—a dynamic usually omitted in the equation portraying Clinton’s impeachment solely as a self-inflicted wound for Republicans. Those doubts led the Gore campaign to conclude they could neither campaign with Clinton nor deploy him extensively as a surrogate.

“It wasn’t just impeachment, it was the feeling that Clinton wasn’t telling the truth to people,” Devine said. “Gore was hurt by that association. Everybody who said the economy was so good, you should just run on Clinton’s record—they weren’t sitting in focus groups in swing states, listening to these swing voters who were concerned there would be a continuation of that [behavior].”

Both Devine and Dowd noted that Bush’s constant pledge to restore presidential honor and dignity skillfully tapped that unease without fully embracing the divisiveness of impeachment itself. “It became a very valuable tool even though Bush didn’t go around saying ‘impeachment, impeachment,’” Devine said. “He took the bad stuff from impeachment and put it front and center [in the campaign]. What could Gore say? ‘I’ll restore honor too’?”

The exit polls in 2000 showed how much that refrain helped Bush with voters conflicted about Clinton. Gore carried 85 percent of the voters who both approved of Clinton’s job performance and expressed favorable views of him personally. But Bush carried one-third of the voters who liked Clinton’s performance but disliked him personally. That’s a much higher-than-usual level of defection from the president’s party among voters who approve of his performance, and in 2000, those voters represented about one-fifth of the entire electorate.

Bush reaped another benefit from the impeachment, Dowd believes: high turnout among Republicans frustrated that Clinton remained in office. “The lack of success on impeachment created a greater hunger, a greater motivation among the base to exact punishment in some way,” said Dowd, now the chief political analyst for ABC News. “And Al Gore became part of that process.”

Despite widespread satisfaction with the economy, all of these factors helped Bush finish just behind Gore in the popular vote and win the Electoral College (after the disputed recount in Florida). Though Republicans lost another two House seats in 2000, they again maintained control of the chamber’s majority—and again narrowly won the nationwide House popular vote. Only in the Senate did the GOP slip, losing five seats that initially created a 50–50 tie until Jeffords’s switch gave Democrats a majority.

Democrats Learned the Wrong Lesson From Clinton’s Impeachment

It didn’t actually cost the GOP all that much.

It didn’t actually cost the GOP all that much.

Democrats debating whether to impeach Donald Trump may be misreading the evidence from the last time the House tried to remove a president.

It’s become conventional wisdom—not only among Democrats but also among many political analysts—that House Republicans paid a severe electoral price for moving against Bill Clinton in 1998, at a time when polls showed most of the public opposed that action.

But that straightforward conclusion oversimplifies impeachment’s effects, according to my analysis of the election results and interviews with key strategists who were working in national politics at the time. While Republicans did lose House seats in both 1998 and 2000, Democrats did not gain enough to capture control of the chamber either time. And in 2000, lingering unease about Clinton’s behavior provided a crucial backdrop for George W. Bush’s winning presidential campaign—particularly his defining promise “to restore honor and dignity” to the Oval Office.

Matthew Dowd, a senior strategist for Bush’s 2000 campaign, told me that Democrats today “are learning the wrong lessons” from Clinton’s impeachment by neglecting to consider how it shaped both election cycles, especially the presidential race. In January 2001, almost exactly two years after House Republicans defied public opinion to impeach Clinton, the GOP controlled the White House, the House, and initially the Senate. (Within months, the Republican Jim Jeffords of Vermont would switch parties, shifting control to the Democrats.) “Having gone through all that,” Dowd said, “I think the Democrats are way too skittish on impeachment.”

Tad Devine, a senior strategist for Al Gore, the Democratic nominee in 2000, concurs. Bush’s ability to tap the public’s dismay over Clinton’s personal life “more than anything else got in our way in terms of winning the election,” he told me. Even if the Senate doesn’t convict Trump, Devine believes, impeachment in the House could offer Democrats a similar chance to highlight the aspects of Trump’s volatile behavior that most alienate swing voters.

“If impeachment is done properly, then the Democratic nominee will be talking about it [next year] and not be running away from it in the general election,” he said. “I don’t look at it as something that is going to derail a Democratic nominee. Just like we saw in 2000, an impeachment inquiry could very badly damage somebody who is associated with it.”

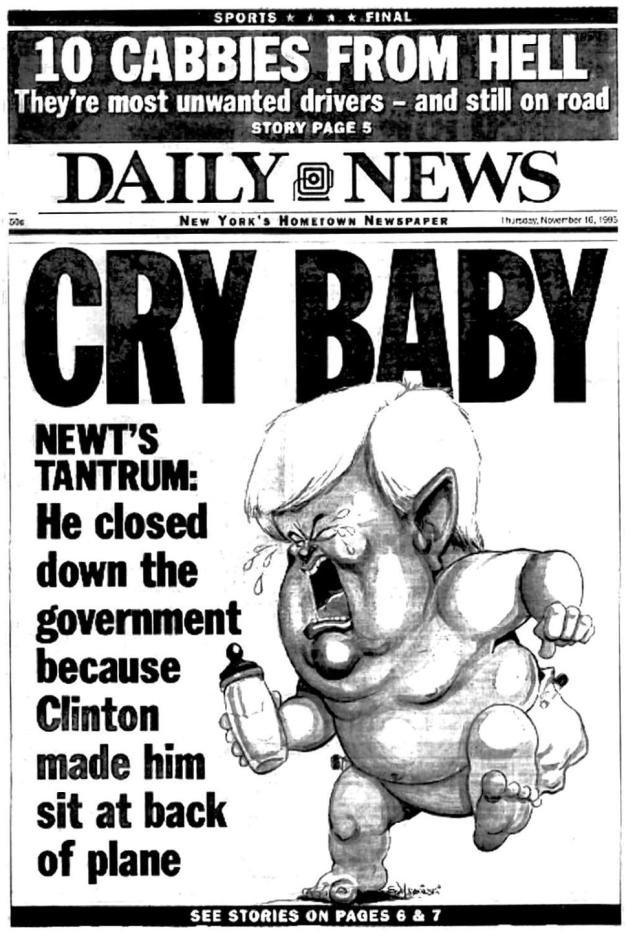

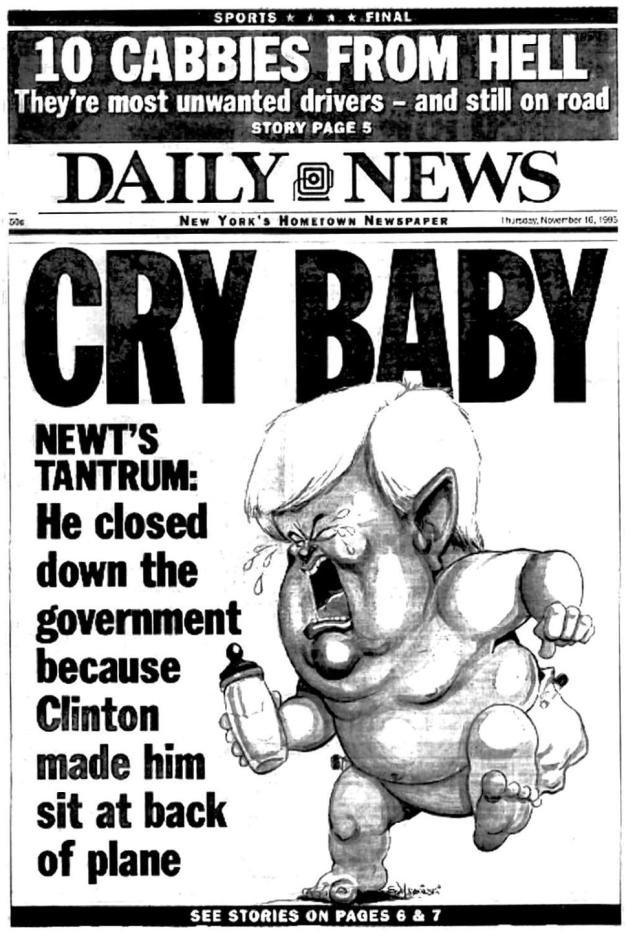

The notion that impeaching Clinton hurt the Republican Party isn’t entirely a myth. The House Republican majority voted to formally begin an impeachment inquiry in October 1998, just weeks before the midterm elections. GOP leaders confidently predicted that public revulsion with Clinton would lead to big Republican gains. “The Republicans were all full of themselves going into the election,” says then–Democratic Representative Martin Frost of Texas, who chaired the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee that year. “They expected to pick up 20 or 30 seats.” Instead, in November, Democrats gained five—the first time a president’s party had won House seats in the sixth year of his tenure since Andrew Jackson in 1834.

But it’s easy to overstate the magnitude of the GOP’s backslide in 1998. In the Senate, Democrats gained no seats that year, leaving the Republican majority intact. Nor did the five-seat House loss cost the GOP its majority in that chamber. Republicans still won more of the total national popular vote in House races than Democrats. Swing voters didn’t stampede away from the GOP; in exit polls, Republicans still narrowly beat Democrats among independent voters. And while impeachment provoked big turnout from African Americans, Clinton’s most passionate supporters, overall, turnout that year was very low.

The midterm election was widely seen as a red light from the public on impeachment. But Republicans barreled ahead and voted in mid-December to remove Clinton anyway. On the day they did so, there was about as much public support for impeaching Clinton as there is today for impeaching Trump. A Gallup poll at the time showed that 35 percent of the public overall backed impeachment, including 40 percent of independents. In a CNN poll this week, 41 percent of the public supported impeachment, including 35 percent of independents. Overall, Clinton’s public support in Gallup polling was much stronger at the time (63 percent job-approval rating) than Trump’s is now (40 percent).

After the Senate refused to remove him in early 1999, Clinton’s job approval remained about a buoyant 60 percent through the rest of his presidency. But that strong number coexisted with substantial public disapproval of the personal behavior that the Starr investigation and the impeachment inquiry had highlighted.

Those personal doubts about the outgoing president cast a huge shadow over the election to succeed him—a dynamic usually omitted in the equation portraying Clinton’s impeachment solely as a self-inflicted wound for Republicans. Those doubts led the Gore campaign to conclude they could neither campaign with Clinton nor deploy him extensively as a surrogate.

“It wasn’t just impeachment, it was the feeling that Clinton wasn’t telling the truth to people,” Devine said. “Gore was hurt by that association. Everybody who said the economy was so good, you should just run on Clinton’s record—they weren’t sitting in focus groups in swing states, listening to these swing voters who were concerned there would be a continuation of that [behavior].”

Both Devine and Dowd noted that Bush’s constant pledge to restore presidential honor and dignity skillfully tapped that unease without fully embracing the divisiveness of impeachment itself. “It became a very valuable tool even though Bush didn’t go around saying ‘impeachment, impeachment,’” Devine said. “He took the bad stuff from impeachment and put it front and center [in the campaign]. What could Gore say? ‘I’ll restore honor too’?”

The exit polls in 2000 showed how much that refrain helped Bush with voters conflicted about Clinton. Gore carried 85 percent of the voters who both approved of Clinton’s job performance and expressed favorable views of him personally. But Bush carried one-third of the voters who liked Clinton’s performance but disliked him personally. That’s a much higher-than-usual level of defection from the president’s party among voters who approve of his performance, and in 2000, those voters represented about one-fifth of the entire electorate.

Bush reaped another benefit from the impeachment, Dowd believes: high turnout among Republicans frustrated that Clinton remained in office. “The lack of success on impeachment created a greater hunger, a greater motivation among the base to exact punishment in some way,” said Dowd, now the chief political analyst for ABC News. “And Al Gore became part of that process.”

Despite widespread satisfaction with the economy, all of these factors helped Bush finish just behind Gore in the popular vote and win the Electoral College (after the disputed recount in Florida). Though Republicans lost another two House seats in 2000, they again maintained control of the chamber’s majority—and again narrowly won the nationwide House popular vote. Only in the Senate did the GOP slip, losing five seats that initially created a 50–50 tie until Jeffords’s switch gave Democrats a majority.