Question:

If eggs are so expensive due to a loss of egg producing chickens due to disease, then why is chicken meat so cheap in grocery stores today?

The disparity between high egg prices and relatively low chicken meat prices, despite disease affecting poultry, stems from several key factors tied to the differing production systems, lifecycles, and market dynamics of egg-laying hens (layers) and chickens raised for meat (broilers).

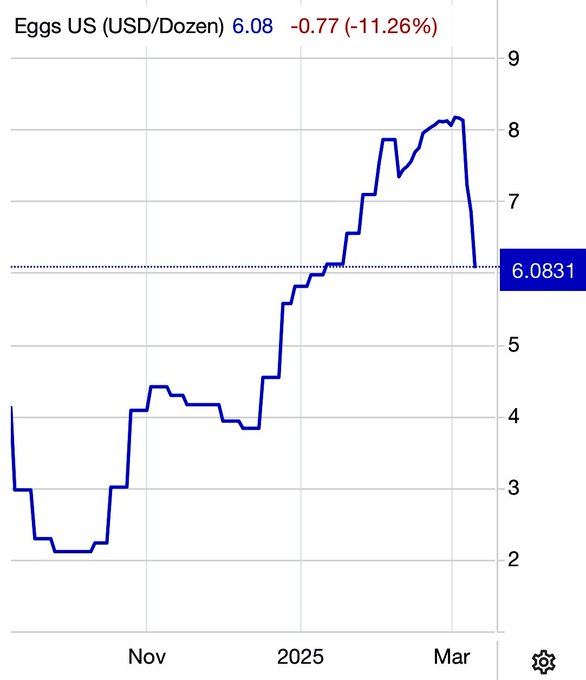

First, the disease in question—highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), or bird flu—has disproportionately impacted egg-laying hens. Since 2022, over 166 million birds have been affected in the U.S., with around 130 million being layers, according to USDA data. When bird flu is detected in a flock, U.S. regulations require culling the entire flock to prevent spread, devastating egg supply. Layers take about 19-20 weeks to mature and start producing eggs, and their productive life spans over a year. Replacing a culled flock thus takes months, leading to prolonged supply shortages and price spikes—egg prices hit $4.95 per dozen in January 2025, per the Bureau of Labor Statistics, up from $2.52 at the start of 2024.

In contrast, broilers—chickens bred for meat—have a much shorter lifecycle, reaching market weight in just 6-8 weeks. The U.S. raises about 9.4 billion broilers annually, dwarfing the 300-320 million layer population. Even when bird flu hits broiler flocks, the losses (e.g., 300,000 birds) are a tiny fraction of this total, and replacements come online quickly, minimizing supply disruption. Moreover, HPAI strains currently circulating are less likely to affect younger birds like broilers, thriving instead in older, longer-lived birds like layers, as noted by agricultural economists.

Second, supply elasticity plays a role. Egg supply is relatively inelastic—slow to adjust due to the long replacement time and smaller flock sizes (often 100,000+ per farm). Broiler supply is more elastic, with massive scale (some farms house 500,000+ birds) and rapid turnover buffering losses. Frozen chicken stockpiles further stabilize meat supply, while eggs, being perishable, lack this buffer—freezing isn’t viable for shell eggs sold at retail.

Third, demand dynamics differ. Eggs have few direct substitutes, especially in baking, and demand remains steady even as prices soar (up 96% in the past year). Chicken meat, however, competes with beef, pork, and plant-based proteins, keeping price increases modest (less than 4% over the same period). Global chicken supply is also high, with exports and imports smoothing domestic shortages.

Finally, culled birds don’t enter the meat supply. Federal rules mandate destruction of infected or exposed flocks to curb disease spread, so millions of dead layers don’t become cheap chicken meat. Broiler prices thus reflect a robust, separate supply chain, not a flood of culled hens.

In short, egg prices are sky-high because bird flu has slashed layer numbers, and recovery is slow. Chicken meat stays cheap because broilers are numerous, fast-growing, less affected, and supported by a flexible, global market—keeping supply steady despite the disease.

@Grok