The rapid shutdown of consumer–facing businesses makes this downturn unique. When cheaper foreign labor lured manufacturing jobs overseas, the U.S. became a service economy.

In March and early April, as the novel coronavirus began killing Americans, shops and businesses closed overnight. Millions of workers—-waitresses and nannies and hotel clerks and line cooks—were instantly out of work.

College-educated employees who can work remotely have, so far, largely been spared, still drawing paychecks and watching their savings grow as they cancel vacations and dinners out and complain about how boring it is to stay at home.

One analysis of unemployment–insurance claims in California found that nearly 37% of workers with just a high school diploma have filed for benefits since March 15, compared with less than 6% of those with a bachelor’s degree.

That may change, of course. No group is safe in a recession of this magnitude. Yelp, Gap and Lyft each cut more than 1,000 corporate employees, and millions more have been furloughed or seen their pay reduced.

But college-educated workers are more likely to have a cushion: they experienced wage gains since 2000 that passed those who make less. Only about 1 in 4 adults in lower-income households say they have enough money to cover expenses for three months in the case of an emergency, according to an April survey by Pew. For upper–income households, the number is 3 in 4.

While the ups and downs of the American economy have long been most destructive to the poor and middle class, this downturn is even more targeted: it is singularly affecting those who can least afford it.

During the Great Recession, while pain was widespread across industries, many service workers kept their jobs as consumers decided a dinner out or a haircut were small luxuries they could afford.

This time, the majority of people laid off are working–class and disproportionately women and people of color, who had been living paycheck to paycheck, their expenses rising while their wages stagnated. One lost job or missed rent payment threatens to tip them into an economic abyss.

Much of the country teeters behind them. The number of new COVID-19 cases shows no sign of receding, and consumers and businesses remain nervous about returning to the way things were.

In the world of finance and business, nothing is less welcome than uncertainty. As the crisis lengthens and consumers continue to delay purchases, more businesses will fail, creating more unemployment and further diminishing consumer demand.

The safety net—already a dubious -patchwork—grows more tattered. In normal times, not quite a third of workers who have lost jobs receive jobless benefits.

In April and May, thousands waited weeks to get through to unemployment offices, sometimes only to be told they weren’t eligible.

Then there is the added expense of health care. About 12.7 million Americans have likely lost employer–provided health insurance since the pandemic began, according to the Economic Policy Institute, adding to the 27.5 million who didn’t have it before this crisis.

When adjusted for inflation, the wages of workers in the bottom tenth of the U.S. economy have risen just 3% since 2000, while those in the top tenth have risen 15.7%, according to the Pew Research Center.

This stagnation, aggravated by the decline in labor unions, is driven by a rise in jobs without guaranteed hours, benefits or even pay.

Retail and food-service workers get called in only if customers show up. The pandemic has reduced most of their hours to zero.

Across the economy, a growing number of workers—from truck drivers to researchers at Google—are independent contractors without the stability and protections of full-time employees. The same is true in the gig economy.

Drivers for apps like Instacart, Uber, Lyft and Amazon Flex don’t know if they’ll make minimum wage on any given day after expenses. And yet, economic desperation drives more people to gig work, diluting the opportunities for all.

There’s no reason to believe that the conditions that led us here will change on their own.

Already, more companies are talking about replacing workers with machines.

And recessions are not good for workers’ leverage. With millions of people now desperate for any income at all, companies can offer less and demand more.

https://time.com/5833008/us-unemployment-coronavirus/

In March and early April, as the novel coronavirus began killing Americans, shops and businesses closed overnight. Millions of workers—-waitresses and nannies and hotel clerks and line cooks—were instantly out of work.

College-educated employees who can work remotely have, so far, largely been spared, still drawing paychecks and watching their savings grow as they cancel vacations and dinners out and complain about how boring it is to stay at home.

One analysis of unemployment–insurance claims in California found that nearly 37% of workers with just a high school diploma have filed for benefits since March 15, compared with less than 6% of those with a bachelor’s degree.

That may change, of course. No group is safe in a recession of this magnitude. Yelp, Gap and Lyft each cut more than 1,000 corporate employees, and millions more have been furloughed or seen their pay reduced.

But college-educated workers are more likely to have a cushion: they experienced wage gains since 2000 that passed those who make less. Only about 1 in 4 adults in lower-income households say they have enough money to cover expenses for three months in the case of an emergency, according to an April survey by Pew. For upper–income households, the number is 3 in 4.

While the ups and downs of the American economy have long been most destructive to the poor and middle class, this downturn is even more targeted: it is singularly affecting those who can least afford it.

During the Great Recession, while pain was widespread across industries, many service workers kept their jobs as consumers decided a dinner out or a haircut were small luxuries they could afford.

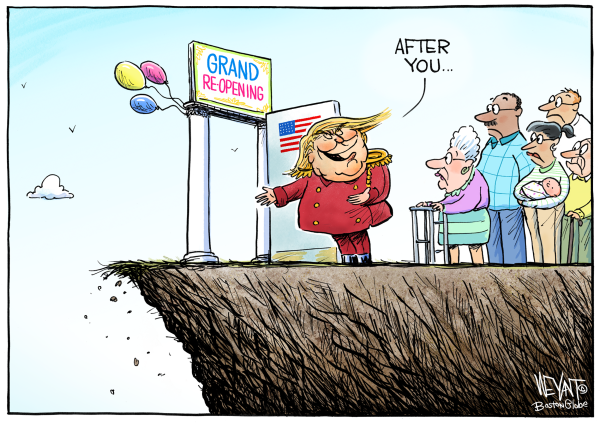

This time, the majority of people laid off are working–class and disproportionately women and people of color, who had been living paycheck to paycheck, their expenses rising while their wages stagnated. One lost job or missed rent payment threatens to tip them into an economic abyss.

Much of the country teeters behind them. The number of new COVID-19 cases shows no sign of receding, and consumers and businesses remain nervous about returning to the way things were.

In the world of finance and business, nothing is less welcome than uncertainty. As the crisis lengthens and consumers continue to delay purchases, more businesses will fail, creating more unemployment and further diminishing consumer demand.

The safety net—already a dubious -patchwork—grows more tattered. In normal times, not quite a third of workers who have lost jobs receive jobless benefits.

In April and May, thousands waited weeks to get through to unemployment offices, sometimes only to be told they weren’t eligible.

Then there is the added expense of health care. About 12.7 million Americans have likely lost employer–provided health insurance since the pandemic began, according to the Economic Policy Institute, adding to the 27.5 million who didn’t have it before this crisis.

When adjusted for inflation, the wages of workers in the bottom tenth of the U.S. economy have risen just 3% since 2000, while those in the top tenth have risen 15.7%, according to the Pew Research Center.

This stagnation, aggravated by the decline in labor unions, is driven by a rise in jobs without guaranteed hours, benefits or even pay.

Retail and food-service workers get called in only if customers show up. The pandemic has reduced most of their hours to zero.

Across the economy, a growing number of workers—from truck drivers to researchers at Google—are independent contractors without the stability and protections of full-time employees. The same is true in the gig economy.

Drivers for apps like Instacart, Uber, Lyft and Amazon Flex don’t know if they’ll make minimum wage on any given day after expenses. And yet, economic desperation drives more people to gig work, diluting the opportunities for all.

There’s no reason to believe that the conditions that led us here will change on their own.

Already, more companies are talking about replacing workers with machines.

And recessions are not good for workers’ leverage. With millions of people now desperate for any income at all, companies can offer less and demand more.

https://time.com/5833008/us-unemployment-coronavirus/