cawacko

Well-known member

Political parties and voters are never static. I don't think what is being stated is set in stone, and could easily revert back, but signs are pointing in this direction.

New fault lines are emerging in American society based more on class than race.

The shift helped deliver the White House to Donald Trump and could continue to alter the political landscape if more Americans identify themselves less in the context of race and gender and more as belonging to a certain economic class.

“Race is not an issue for me,” said Aaron Waters, a Black unionized construction worker in Chicago who voted for Trump after voting for President Biden and Barack Obama in past elections. “It’s about what you can do for each and every one of us as a whole, as a U.S. citizen.”

Trump made gains with most demographic groups in this month’s election. But one of the biggest swings was among voters of all races who don’t have a four-year college degree. He won them by 13 percentage points this time versus 4 percentage points in 2020—a huge change in a group that accounted for more than half of the electorate. College-educated voters of all races also swung to Trump, but to a much smaller degree.

Aaron Waters, a unionized construction worker in Chicago, voted for Donald Trump. Photo: Akilah Whitmore for WSJ

Aaron Waters, a unionized construction worker in Chicago, voted for Donald Trump. Photo: Akilah Whitmore for WSJ

Black and to a greater extent Latino Americans, meanwhile, ceded some of their longtime allegiance to Democrats. Trump gained with nonwhite voters of all education levels, but he made bigger gains with those who don’t have degrees than with those who do.

Overall voting patterns still clearly reflect racial division. Black voters overwhelmingly backed Harris, and a slim majority of Latino voters did, too. William Frey, a Brookings Institution demographer, said the voting shifts could be a “blip” related to sharp inflation, and that it is too soon “to predict a multiracial transformation of the GOP.”

There is evidence the shift in voting patterns predates this election. In 2022, for instance, voters in Detroit, a majority Black city, elected a non-Black representative to Congress for the first time in 70 years. Many cited economic concerns as a primary driver behind their decisions.

“This is the shock of the early 21st century,” said Todd Shaw, associate professor of political science and African-American studies at the University of South Carolina. Shaw said for many minority voters, economic anxiety often outweighs other political considerations, especially in the wake of a global pandemic that hit many working-class voters hard.

The shift toward class-based sorting also comes as some of the nation’s longtime racial categories—white, Black and Hispanic—are dissolving fast into more fluid and complex identities. As those categories blur, other factors, like education levels and class, are playing larger roles in Americans’ quality-of-life and are increasingly driving voters’ choices.

Thirty years ago, Americans with a college degree accounted for roughly 20% of the population and held the same percentage of household wealth as those without a degree, according to the census and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Today, Americans with a college degree account for 38% of the population and 73% of household wealth.

Those with a college degree live nearly nine years longer on average than those without, according to a 2023 study by Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton. The gap has tripled in one generation, from 2.5 years in 1992.

A Latino Summit roundtable was held by the Trump campaign last month in Doral, Fla. Photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

A Latino Summit roundtable was held by the Trump campaign last month in Doral, Fla. Photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Voting patterns among those without a college degree reflect the new fault lines, from white women in suburban Atlanta to Black construction workers and Latino retail employees in Chicago. These voters seem to have little in common on paper, but last week they coalesced around Trump.

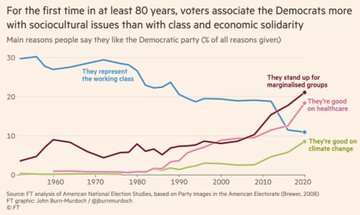

That outcome reflected a shift in the decades-old orientation of the two-party political system. It marked just how successful the Republican Party has been at refashioning its image as the champion for the working class, and served as a warning sign for Democratic Party leadership. This week, Democratic Party veterans Rahm Emanuel and Maine Gov. Janet Mills argued that it was time to stamp out identity politics.

Chicagoan Alfredo Ramirez voted twice for Barack Obama and for Hillary Clinton in 2016. But in the last two elections he has backed Trump.

Ramirez said economic concerns, not race, largely drove his vote this time. He and his wife are raising three children on his $25,000-a-year job at Target. He remembers the economy being better before the pandemic, when eggs and everything else cost less.

Trump “has done more for the American people, as opposed to the Democrats. They are only caring about themselves,” Ramirez said. He said being Latino didn’t affect his vote. “It really doesn’t matter…as long as we are out here fighting for our freedom.”

American political alignment has shifted in big ways before, according to Colby College professor Nicholas F. Jacobs, who said that in the 1980s, it became more important whether a voter lived in an urban or rural area than whether they lived in a particular part of the country, such as the Northeast or Southwest.

He sees evidence of a similar realignment occurring along lines of class in this month’s election, with Republicans making a far better appeal. Democrats at times tried to use statistics, he said, explained down to the decimal point, to argue that inflation wasn’t really hurting people and that voters’ concerns about immigration were unfounded.

“The most important thing about class politics is the sense that you are recognized, you have value in our society, and the person seeking your vote sees you have dignity and worth,” he said.

Biden hoped to bolster support for Democrats among the working class through the federal investments he championed in U.S. infrastructure and manufacturing. Several laws he helped shepherd through Congress devoted tens of billions of dollars to building roads, bridges, factories and electric-vehicle chargers.

Photo: Akilah Whitmore for WSJ

Photo: Akilah Whitmore for WSJ

A project to overhaul Chicago’s ‘L’ train was funded by President Biden’s infrastructure law and employs unionized workers. Photo: Akilah Whitmore for WSJ

A project to overhaul Chicago’s ‘L’ train was funded by President Biden’s infrastructure law and employs unionized workers. Photo: Akilah Whitmore for WSJ

But at one of those construction sites in Chicago this week—a buzzing project to overhaul the city’s elevated train—some laborers said they voted for Trump.

Nicole Wiltz, a 52-year-old Black unionized worker in a hard hat and bright yellow vest, said she usually votes for Democrats but was dismayed to see how many resources the government devoted to the migrant crisis when many longtime Chicagoans were still homeless.

Wiltz said she didn’t feel pressure from her union or friends and family to vote for Harris. Nor did she feel she should because Harris is a Black woman.

“I mean, it’s not about that. It’s about right now,” Wiltz said. She respects the Black community’s tradition of voting for Democrats but said she is fed up with politicians who “don’t deliver what they promised.”

Hispanic and Black voters throughout the country echoed this idea, that notions of fealty to the Democratic Party based on race were outdated—and that economic concerns drove the shift to Republicans and Trump.

Yubisay Camero, a 49-year-old Venezuelan-American in Doral, Fla., said she voted for Trump, as she did in 2020, when she cast her first ballot in a U.S. presidential election. Worries about inflation and illegal immigration, which she said has brought criminals to the country, drove her decision.

Yubisay Camero says concerns about inflation and illegal immigration drove her voting choice. Photo: Eva Marie Uzcategui for WSJ

Yubisay Camero says concerns about inflation and illegal immigration drove her voting choice. Photo: Eva Marie Uzcategui for WSJ

“In the last four years, people have had less and less hope,” said Camero. “It’s not the same economy, in which people who work can get ahead.”

Carelia Spence, a 60-year-old Venezuelan-American and registered independent in Tampa, Fla., said she voted for Trump, her first time participating in a presidential election since becoming a U.S. citizen.

Spence said her finances deteriorated under Biden, and her wages failed to keep up with prices. After working at Home Depot and driving for Uber, she landed a position as an insurance agent and now makes $24 an hour. But her employer recently cut bonuses and profit-sharing, reducing her pay.

Spence said she supported Obama when he was in office, though she wasn’t yet a U.S. citizen. But she said he failed to help average people, and she became disenchanted with Democrats and their message that Republicans don’t care about Hispanics.

“We don’t want that condescension,” Spence said. “We know they use us to win elections. But when the moment comes to do something, they don’t do anything.”

The New Driving Force of Identity Politics Is Class, Not Race

The nation is increasingly voting along class lines, not racial ones. That could upend how we have thought about politics for decades.

New fault lines are emerging in American society based more on class than race.

The shift helped deliver the White House to Donald Trump and could continue to alter the political landscape if more Americans identify themselves less in the context of race and gender and more as belonging to a certain economic class.

“Race is not an issue for me,” said Aaron Waters, a Black unionized construction worker in Chicago who voted for Trump after voting for President Biden and Barack Obama in past elections. “It’s about what you can do for each and every one of us as a whole, as a U.S. citizen.”

Trump made gains with most demographic groups in this month’s election. But one of the biggest swings was among voters of all races who don’t have a four-year college degree. He won them by 13 percentage points this time versus 4 percentage points in 2020—a huge change in a group that accounted for more than half of the electorate. College-educated voters of all races also swung to Trump, but to a much smaller degree.

Black and to a greater extent Latino Americans, meanwhile, ceded some of their longtime allegiance to Democrats. Trump gained with nonwhite voters of all education levels, but he made bigger gains with those who don’t have degrees than with those who do.

Overall voting patterns still clearly reflect racial division. Black voters overwhelmingly backed Harris, and a slim majority of Latino voters did, too. William Frey, a Brookings Institution demographer, said the voting shifts could be a “blip” related to sharp inflation, and that it is too soon “to predict a multiracial transformation of the GOP.”

There is evidence the shift in voting patterns predates this election. In 2022, for instance, voters in Detroit, a majority Black city, elected a non-Black representative to Congress for the first time in 70 years. Many cited economic concerns as a primary driver behind their decisions.

“This is the shock of the early 21st century,” said Todd Shaw, associate professor of political science and African-American studies at the University of South Carolina. Shaw said for many minority voters, economic anxiety often outweighs other political considerations, especially in the wake of a global pandemic that hit many working-class voters hard.

The shift toward class-based sorting also comes as some of the nation’s longtime racial categories—white, Black and Hispanic—are dissolving fast into more fluid and complex identities. As those categories blur, other factors, like education levels and class, are playing larger roles in Americans’ quality-of-life and are increasingly driving voters’ choices.

Thirty years ago, Americans with a college degree accounted for roughly 20% of the population and held the same percentage of household wealth as those without a degree, according to the census and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Today, Americans with a college degree account for 38% of the population and 73% of household wealth.

Those with a college degree live nearly nine years longer on average than those without, according to a 2023 study by Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton. The gap has tripled in one generation, from 2.5 years in 1992.

Voting patterns among those without a college degree reflect the new fault lines, from white women in suburban Atlanta to Black construction workers and Latino retail employees in Chicago. These voters seem to have little in common on paper, but last week they coalesced around Trump.

That outcome reflected a shift in the decades-old orientation of the two-party political system. It marked just how successful the Republican Party has been at refashioning its image as the champion for the working class, and served as a warning sign for Democratic Party leadership. This week, Democratic Party veterans Rahm Emanuel and Maine Gov. Janet Mills argued that it was time to stamp out identity politics.

Chicagoan Alfredo Ramirez voted twice for Barack Obama and for Hillary Clinton in 2016. But in the last two elections he has backed Trump.

Ramirez said economic concerns, not race, largely drove his vote this time. He and his wife are raising three children on his $25,000-a-year job at Target. He remembers the economy being better before the pandemic, when eggs and everything else cost less.

Trump “has done more for the American people, as opposed to the Democrats. They are only caring about themselves,” Ramirez said. He said being Latino didn’t affect his vote. “It really doesn’t matter…as long as we are out here fighting for our freedom.”

American political alignment has shifted in big ways before, according to Colby College professor Nicholas F. Jacobs, who said that in the 1980s, it became more important whether a voter lived in an urban or rural area than whether they lived in a particular part of the country, such as the Northeast or Southwest.

He sees evidence of a similar realignment occurring along lines of class in this month’s election, with Republicans making a far better appeal. Democrats at times tried to use statistics, he said, explained down to the decimal point, to argue that inflation wasn’t really hurting people and that voters’ concerns about immigration were unfounded.

“The most important thing about class politics is the sense that you are recognized, you have value in our society, and the person seeking your vote sees you have dignity and worth,” he said.

Biden hoped to bolster support for Democrats among the working class through the federal investments he championed in U.S. infrastructure and manufacturing. Several laws he helped shepherd through Congress devoted tens of billions of dollars to building roads, bridges, factories and electric-vehicle chargers.

But at one of those construction sites in Chicago this week—a buzzing project to overhaul the city’s elevated train—some laborers said they voted for Trump.

Nicole Wiltz, a 52-year-old Black unionized worker in a hard hat and bright yellow vest, said she usually votes for Democrats but was dismayed to see how many resources the government devoted to the migrant crisis when many longtime Chicagoans were still homeless.

Wiltz said she didn’t feel pressure from her union or friends and family to vote for Harris. Nor did she feel she should because Harris is a Black woman.

“I mean, it’s not about that. It’s about right now,” Wiltz said. She respects the Black community’s tradition of voting for Democrats but said she is fed up with politicians who “don’t deliver what they promised.”

Hispanic and Black voters throughout the country echoed this idea, that notions of fealty to the Democratic Party based on race were outdated—and that economic concerns drove the shift to Republicans and Trump.

Yubisay Camero, a 49-year-old Venezuelan-American in Doral, Fla., said she voted for Trump, as she did in 2020, when she cast her first ballot in a U.S. presidential election. Worries about inflation and illegal immigration, which she said has brought criminals to the country, drove her decision.

“In the last four years, people have had less and less hope,” said Camero. “It’s not the same economy, in which people who work can get ahead.”

Carelia Spence, a 60-year-old Venezuelan-American and registered independent in Tampa, Fla., said she voted for Trump, her first time participating in a presidential election since becoming a U.S. citizen.

Spence said her finances deteriorated under Biden, and her wages failed to keep up with prices. After working at Home Depot and driving for Uber, she landed a position as an insurance agent and now makes $24 an hour. But her employer recently cut bonuses and profit-sharing, reducing her pay.

Spence said she supported Obama when he was in office, though she wasn’t yet a U.S. citizen. But she said he failed to help average people, and she became disenchanted with Democrats and their message that Republicans don’t care about Hispanics.

“We don’t want that condescension,” Spence said. “We know they use us to win elections. But when the moment comes to do something, they don’t do anything.”