In Libya's south, the Tuareg, a Berber ethnic group, are using the conflict to build their sphere of influence, counteracting decades of social stigma and reasserting their national identity.

https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/i...t-conflict-is-raging-in-libyas-desertic-south

Tuareg tribesmen sit together during a traditional ceremony in the Libyan desert [Getty]

Eight years after the death of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, two factions are still fighting for control of Libya.

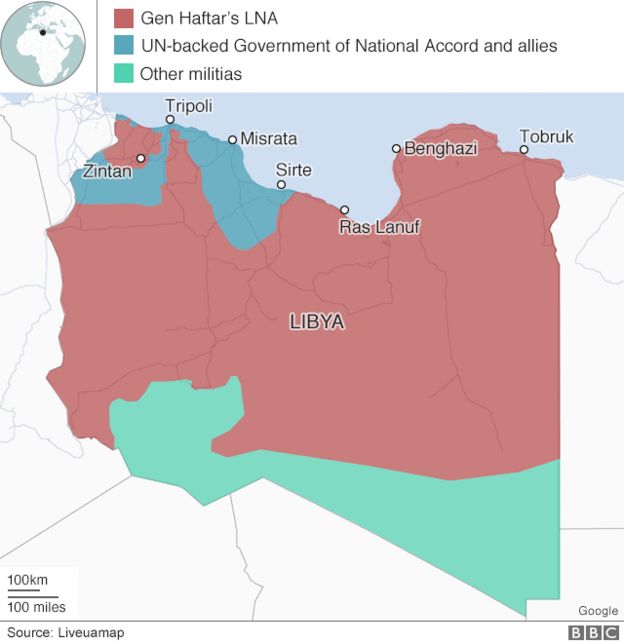

In the western city of Tripoli, Libya's capital, the Government of National Accord (GNA) under Libyan Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj has gained diplomatic recognition from the United Nations but struggled to establish itself on the ground, reliant on support from a constellation of Libyan militias.

In the east, the would-be strongman Khalifa Haftar has used his own militia, the Libyan National Army (LNA), to conquer the cities of Benghazi and Derna and launch an offensive on Tripoli.

While the best-known battles of the Libyan Civil War have remained confined to Libya's coast, home to most of the country's population, a quiet conflict has been raging in the desertic south.

There, the GNA and the LNA have competed for the allegiance of several non-Arab ethnic groups. They include the Tuareg, a minority group with a history of marginalisation at the hands of the Libyan state.

Often considered a subgroup of the Berbers, a North African people, the Tuareg form a sizeable minority in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. An additional community inhabits the southern Libyan region of Fezzan, where nomadic Tuareg tribes have worked as merchants and smugglers for millennia.

Gaddafi encouraged the immigration of Tuareg from Mali and Niger and recruited them into his military, through which some Tuareg acquired Libyan citizenship.

The eccentric autocrat heralded them as "Arabs of the south," yet he also discriminated against them, expelling thousands from Libya in the 1980s.

"Before the Libyan conflict, the Tuareg were divided between those with Libyan citizenship and those without," said Claudia Gazzini, the International Crisis Group's senior analyst for Libya. "Gaddafi nonetheless employed citizens and non-citizens alike in his security agencies."

Gaddafi incorporated the Tuareg into his erratic foreign policy, training some to rebel against his Malian and Nigerien rivals. The minority also inspired his notorious, mansion-sized tent.

"The Tuareg fascinated Gaddafi," said Dr Igor Cherstich, a social anthropologist at University College London and author of an upcoming book on the Libyan Revolution.

"Gaddafi romanticised the Tuareg lifestyle, one example being the tent that he always used during travel abroad. Even so, Gaddafi frequently described the Tuareg as Arabs, completely reinventing their identity."

Gaddafi romanticised the Tuareg lifestyle, one example being the tent that he always used during travel abroad. Even so, Gaddafi frequently described the Tuareg as Arabs, completely reinventing their identity

As Gaddafi fought a losing battle against rebels in his own country, some of the Libyan, Malian, and Nigerien Tuareg whom he had bankrolled over the years supported him during his last stand.

When Libyan rebels killed Gaddafi in October 2011, many of the West African Tuareg who had joined his army returned to their countries of origin. Libyan Tuareg, however, suffered reprisals from Arab neighbours who backed the rebellion and blamed the minority as a whole for the actions of pro-Gaddafi Tuareg.

"Under the Gaddafi regime, the Tuareg were partially integrated into a brigade of the Libyan Army called the Islamic Legion," said Dr Ricardo René Larémont, a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and a professor of sociology at Binghamton University.

"With the fall of Gaddafi, they lost their erstwhile patron and are largely fending for their own in southern Libya and eastern Mali."

Though Gaddafi had offered the Tuareg opportunities for advancement, he had also deprived the minority of its culture. The pan-Arab strongman had refused to recognise the distinctiveness of the Tuareg ethnicity, but, with his death, Tuareg began asserting their rights and forming associations.

"After the revolution, the Tuareg – and more generally Libyan Berbers – finally felt free to celebrate their cultural heritage," Cherstich told The New Arab.

Prior to the Libyan Revolution, Gaddafi had oppressed his country's minorities, declaring in 2010 that Berbers "no longer existed."

Many Berbers viewed the rebellion against him as a rare opportunity to reclaim their cultural heritage after decades of Arabisation. Following the fall of Gaddafi's government, Berber veterans of the war against him celebrated by placing their flags in cities across Libya.

"It is important to understand that the Tuareg are a Berber ethnic confederation – though, in Libya, they often stress that their identity differs from that of coastal Berbers," said Cherstich. "Under Gaddafi, Berbers were discouraged from using their language and expressing their own culture."

As Libyan warlords backed by regional powers took advantage of the power vacuum sparked by Gaddafi's death, Libya's minorities soon realised that they had little reason to rejoice.

Amid the country's descent into chaos, few of the country's new leaders seemed concerned with the wellbeing of the Tuareg.

Instead, well-armed militias prioritised capturing Libya's oil reserves, ousting the Islamic State group (IS) from the Libyan coast, and trafficking migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa to the Mediterranean Sea.

"The Tuareg were controlled and used by Gaddafi, excluded from the most important positions of the regime, and too many times forgotten," said Dr Federica Saini Fasanotti, a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of Libya 1922–1931: The Italian Counterinsurgency.

"Sarraj has tried to be more inclusive, but certainly what has been done so far cannot be called sufficient."

Under Gaddafi, Berbers were discouraged from using their language and expressing their own culture

Rather than uniting the Tuareg and other Libyan minorities, the aftermath of Gaddafi's downfall has divided the fractious ethnicities further. Just as Tuareg fought on both sides of the Libyan Revolution, they have spent the last eight years clashing with each other on behalf of rival Libyan governments.

"The two main Libyan coalitions are trying to entice Tuareg fighters with offers of citizenship and payment," said Gazzini. "This time, the Tuareg are divided between the LNA and the GNA."

In addition to the internal divisions created by the Libyan Civil War, the Tuareg have battled the Tebu, another minority in Fezzan, and the Awlad Suleiman, a southern Arab tribe.