Called responsible parenting.It's almost like there might be socio-economic reasons for stuff...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Violent crime rates by race

- Thread starter volsrocks

- Start date

Called responsible parenting.

What is?

BartenderElite

Verified User

Called responsible parenting.

Huh?

BartenderElite

Verified User

Divide the crime rate by wealth and you get a different slant. The poor commit crimes to survive. The wealthy loot because they can.

Once in awhile, there is a bit of logic on this board.

Thomas Sowell, an economist and social theorist, has written extensively about the topic of black crime in America, often challenging prevailing narratives and focusing on data-driven analysis and cultural factors rather than attributing disparities solely to racism or systemic injustice.

His views are rooted in a broader critique of social policies, cultural attitudes, and historical context.

Below is a summary of key points he has made on this subject based on his writings and interviews:

Crime Rates and Statistical Context: Sowell argues that the disproportionate involvement of black individuals in crime, particularly violent crimes like homicide, cannot be fully understood by simply comparing arrest rates to population percentages (e.g., blacks making up about 13% of the U.S. population but a much higher percentage of arrests).

He emphasizes that the relevant comparison is not the general population but the rate at which specific groups commit crimes.

For instance, he has noted that the homicide rate among black Americans has historically been a multiple of that among white Americans, suggesting that higher arrest or incarceration rates reflect real differences in behavior rather than just police targeting or systemic bias.

Cultural Influences Over Racism

Sowell frequently points to cultural factors rather than racism as a primary driver of black crime rates. In works like Black Rednecks and White Liberals, he posits that much of what is considered "black ghetto culture" originated from the violent, anti-educational, and honor-driven subculture of white Southern "rednecks" in the antebellum South, which was transmitted to enslaved black populations and persisted over time.

He argues that this cultural heritage—marked by touchy pride, resistance to authority, and a lack of emphasis on education or entrepreneurship—has had a more lasting impact on crime rates than slavery or discrimination alone.

Historical Trends and Policy Impacts

Sowell highlights that black crime rates were lower in earlier periods, such as the 1940s and 1950s, despite higher poverty and more overt racism.

He contrasts this with the post-1960s era, where crime rates, particularly murder rates, surged alongside the expansion of the welfare state.

He suggests that policies starting in the 1960s, such as welfare programs that reduced incentives for two-parent households, contributed to family breakdown, which he sees as a significant factor in rising crime.

For example, he notes that murder rates among black males doubled after the 1960s, while the proportion of black children raised in single-parent homes increased dramatically.

Family Structure

Sowell consistently links the disintegration of the black family to higher crime rates.

He points out that before the 1960s, most black children were raised in two-parent families, but by the late 20th century, the majority were raised by single parents. He argues that this shift, exacerbated by welfare policies that disincentivized marriage, left many young black males without the stabilizing influence of fathers, correlating with increased criminality.

Rejection of the "Legacy of Slavery" Narrative: Sowell disputes the common claim that current black crime rates are primarily a "legacy of slavery."

He argues that if slavery were the main cause, crime rates should have been higher in the decades immediately following emancipation when its effects were more direct. Instead, he observes that social problems like crime and family breakdown worsened significantly after the 1960s, suggesting that modern social policies and cultural shifts bear more responsibility.

Critique of Liberal Explanations: Sowell challenges what he sees as overly simplistic explanations from white liberals and civil rights advocates who attribute black crime solely to white racism or poverty.

He contends that this perspective ignores evidence of black progress before the 1960s and excuses individual behavior by framing blacks as perpetual victims. In Intellectuals and Race, he criticizes the tendency to overlook cultural and behavioral factors in favor of a narrative that blames external forces, which he believes hinders effective solutions.

@Grok

His views are rooted in a broader critique of social policies, cultural attitudes, and historical context.

Below is a summary of key points he has made on this subject based on his writings and interviews:

Crime Rates and Statistical Context: Sowell argues that the disproportionate involvement of black individuals in crime, particularly violent crimes like homicide, cannot be fully understood by simply comparing arrest rates to population percentages (e.g., blacks making up about 13% of the U.S. population but a much higher percentage of arrests).

He emphasizes that the relevant comparison is not the general population but the rate at which specific groups commit crimes.

For instance, he has noted that the homicide rate among black Americans has historically been a multiple of that among white Americans, suggesting that higher arrest or incarceration rates reflect real differences in behavior rather than just police targeting or systemic bias.

Cultural Influences Over Racism

Sowell frequently points to cultural factors rather than racism as a primary driver of black crime rates. In works like Black Rednecks and White Liberals, he posits that much of what is considered "black ghetto culture" originated from the violent, anti-educational, and honor-driven subculture of white Southern "rednecks" in the antebellum South, which was transmitted to enslaved black populations and persisted over time.

He argues that this cultural heritage—marked by touchy pride, resistance to authority, and a lack of emphasis on education or entrepreneurship—has had a more lasting impact on crime rates than slavery or discrimination alone.

Historical Trends and Policy Impacts

Sowell highlights that black crime rates were lower in earlier periods, such as the 1940s and 1950s, despite higher poverty and more overt racism.

He contrasts this with the post-1960s era, where crime rates, particularly murder rates, surged alongside the expansion of the welfare state.

He suggests that policies starting in the 1960s, such as welfare programs that reduced incentives for two-parent households, contributed to family breakdown, which he sees as a significant factor in rising crime.

For example, he notes that murder rates among black males doubled after the 1960s, while the proportion of black children raised in single-parent homes increased dramatically.

Family Structure

Sowell consistently links the disintegration of the black family to higher crime rates.

He points out that before the 1960s, most black children were raised in two-parent families, but by the late 20th century, the majority were raised by single parents. He argues that this shift, exacerbated by welfare policies that disincentivized marriage, left many young black males without the stabilizing influence of fathers, correlating with increased criminality.

Rejection of the "Legacy of Slavery" Narrative: Sowell disputes the common claim that current black crime rates are primarily a "legacy of slavery."

He argues that if slavery were the main cause, crime rates should have been higher in the decades immediately following emancipation when its effects were more direct. Instead, he observes that social problems like crime and family breakdown worsened significantly after the 1960s, suggesting that modern social policies and cultural shifts bear more responsibility.

Critique of Liberal Explanations: Sowell challenges what he sees as overly simplistic explanations from white liberals and civil rights advocates who attribute black crime solely to white racism or poverty.

He contends that this perspective ignores evidence of black progress before the 1960s and excuses individual behavior by framing blacks as perpetual victims. In Intellectuals and Race, he criticizes the tendency to overlook cultural and behavioral factors in favor of a narrative that blames external forces, which he believes hinders effective solutions.

Empirical Examples: Sowell often uses data to support his arguments.

For instance, he has cited that between 1976 and 2005, blacks committed over half of all murders in the U.S., despite being a small fraction of the population.

He also points to the success of black married couples—whose poverty rates have been in single digits since 1994—as evidence that behavior and family structure, not just racism, shape outcomes.

For instance, he has cited that between 1976 and 2005, blacks committed over half of all murders in the U.S., despite being a small fraction of the population.

He also points to the success of black married couples—whose poverty rates have been in single digits since 1994—as evidence that behavior and family structure, not just racism, shape outcomes.

In summary, Thomas Sowell views black crime in America as a complex issue driven more by cultural legacies, family structure, and misguided social policies than by racism or slavery.

He advocates for addressing these root causes rather than relying on what he considers superficial explanations or government interventions that, in his view, often worsen the problem.

His perspective is grounded in historical analysis and statistical evidence, aiming to shift the focus from blame to understanding and practical solutions.

He advocates for addressing these root causes rather than relying on what he considers superficial explanations or government interventions that, in his view, often worsen the problem.

His perspective is grounded in historical analysis and statistical evidence, aiming to shift the focus from blame to understanding and practical solutions.

@Grok

Once in awhile, there is a bit of logic on this board.

Thanks! I appreciate the compliment.

Divide the crime rate by wealth and you get a different slant. The poor commit crimes to survive. The wealthy loot because they can.

Dividing crime rates by wealth (e.g., normalizing crime statistics by income levels or socioeconomic status) wouldn’t inherently "prove" that black Americans are less criminal, but it could shift the perspective on crime disparities by highlighting the role of poverty rather than race alone.

Let’s break this down with Thomas Sowell’s insights in mind and some general reasoning based on available data:

Sowell’s Perspective

Thomas Sowell would likely caution against using wealth-adjusted crime rates as a definitive "proof" of anything without careful context. He has consistently argued that crime differences stem more from cultural and behavioral factors—like family structure and internalized subcultures—than from economic conditions alone. For instance:

- Sowell has pointed out that black crime rates were lower in the mid-20th century despite greater poverty and discrimination, suggesting that poverty isn’t a sufficient explanation for criminality.

- He’d likely note that even within similar income brackets, disparities in crime rates persist, which he attributes to cultural differences rather than wealth itself.

Analyzing the Idea

If you divide crime rates by wealth, you’re essentially asking whether black Americans commit crimes at a lower rate than other groups when socioeconomic status is held constant. Here’s how that might play out:

- Poverty and Crime Correlation: Crime, especially violent crime, tends to correlate with poverty across all racial groups. Black Americans are disproportionately represented in lower income brackets—roughly 19% lived below the poverty line in 2022 (U.S. Census data), compared to 8% of non-Hispanic whites. If you adjust crime rates by income, the raw disparity (e.g., blacks committing over 50% of homicides despite being 13% of the population) might shrink because poverty amplifies crime risk universally.

- Within-Income-Group Disparities: Studies and crime data (like FBI Uniform Crime Reports) show that even when controlling for income, black crime rates often remain higher than those of other racial groups in the same economic bracket. For example, a 2011 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that among poor urban residents, black individuals still had higher homicide offending rates than whites or Hispanics. This suggests that wealth adjustment reduces, but doesn’t eliminate, the gap.

- Hypothetical Outcome: If you divided the homicide rate by, say, the poverty rate for each group:

- Black poverty rate: ~19%, homicide rate: ~50% of U.S. total (for 13% of population).

- White poverty rate: ~8%, homicide rate: ~30% of U.S. total (for 60% of population).Normalizing might show black crime rates per poor person are still higher than white rates per poor person, though the gap narrows. Exact numbers depend on the dataset and methodology, but the pattern holds in most analyses.

- Limitations: Wealth doesn’t capture all socioeconomic factors (e.g., education, family structure, neighborhood effects). Sowell would argue that single-parent households—more prevalent among black families (around 64% of black children born to unmarried mothers vs. 24% for whites, per CDC data)—correlate strongly with crime independent of income. Adjusting for wealth alone might obscure these variables.

Does It "Prove" Less Criminality?

- No Definitive Proof: Adjusting for wealth might lower the relative crime rate for black Americans compared to unadjusted stats, potentially aligning it closer to other groups. But "less criminal" implies a reversal of the trend, which data doesn’t typically support—disparities persist even after such adjustments.

- Interpretation Matters: Advocates might argue it "proves" systemic factors like poverty drive crime more than race, aligning with narratives Sowell critiques. Sowell, however, would counter that this overlooks agency, culture, and historical shifts (e.g., rising crime post-1960s despite economic gains).

Conclusion

Dividing crime rates by wealth could suggest poverty plays a bigger role in black crime than raw stats imply, potentially reducing racial disparities in the numbers.

However, it wouldn’t "prove" black Americans are less criminal than others—it would just reframe the question.

Sowell’s view would likely be that such an exercise misses the deeper cultural and behavioral drivers he emphasizes, and the data, even adjusted, wouldn’t fully support a narrative of equal or lower criminality across groups.

For a precise answer, you’d need to run the numbers with current datasets, but the broad patterns suggest adjustment narrows, rather than reverses, the gap.

@Grok

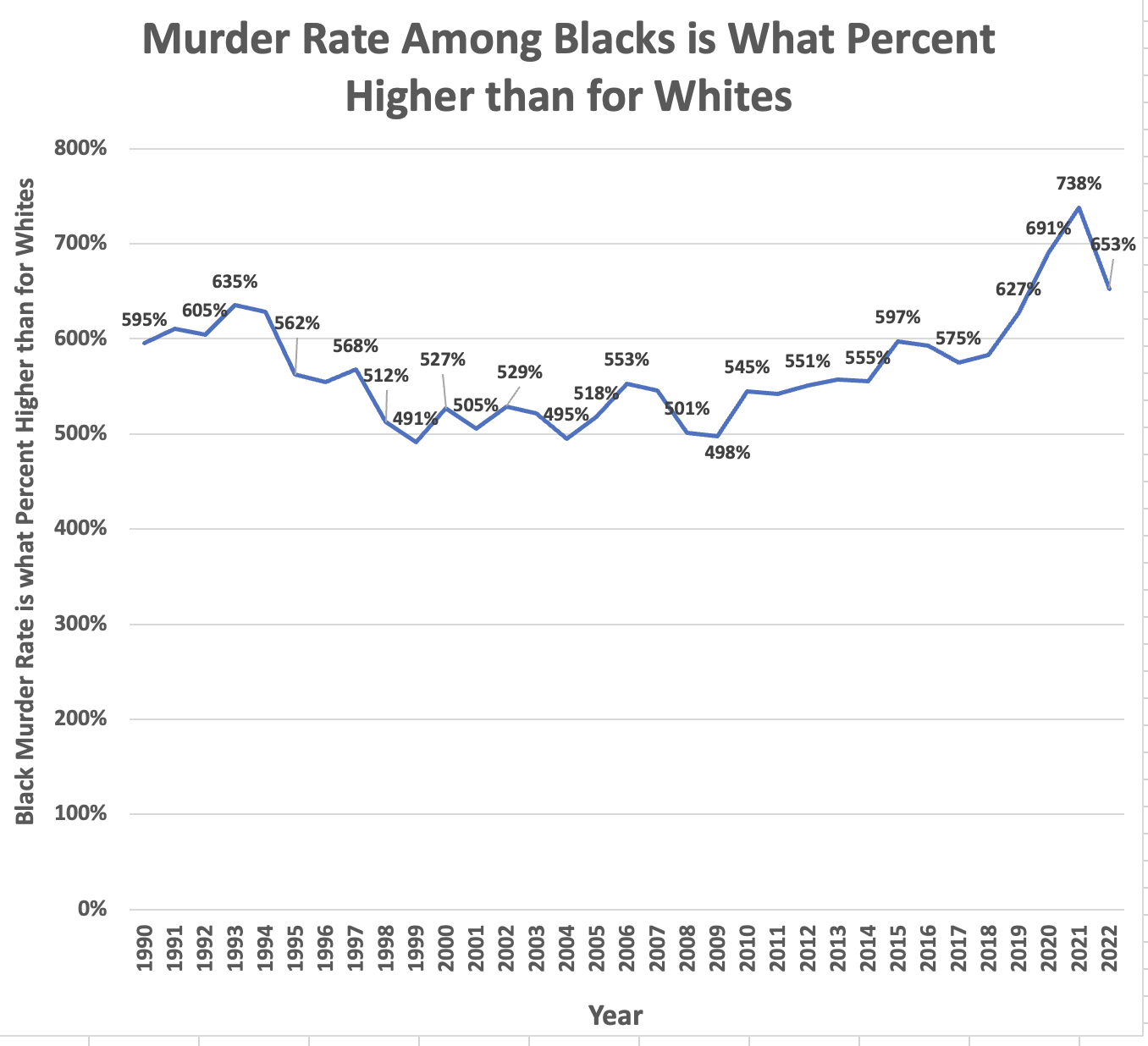

Always comical how all these Red Hat Club racists are so afraid that some kid in a hoodie is going to walk down the street of their gated community somedayIn 2022, the murder rate among blacks is 653% higher than the murder rate for whites. The murder rate for Hispanics is 65% higher than for whites. Nor are those numbers that much of an outlier. From 1990 through 2022, the black murder rate average 569% higher than whites, and the number for Hispanics was 57% higher.

Violent Crime Rates by Race - Crime Prevention Research Center

In 2022, the murder rate among blacks is 653% higher than the murder rate for whites. The murder rate for Hispanics is 65% higher than for whites. Nor arecrimeresearch.org

You do understand facts are rayciss, right?Dividing crime rates by wealth (e.g., normalizing crime statistics by income levels or socioeconomic status) wouldn’t inherently "prove" that black Americans are less criminal, but it could shift the perspective on crime disparities by highlighting the role of poverty rather than race alone.

Let’s break this down with Thomas Sowell’s insights in mind and some general reasoning based on available data:

Sowell’s Perspective

Thomas Sowell would likely caution against using wealth-adjusted crime rates as a definitive "proof" of anything without careful context. He has consistently argued that crime differences stem more from cultural and behavioral factors—like family structure and internalized subcultures—than from economic conditions alone. For instance:

- Sowell has pointed out that black crime rates were lower in the mid-20th century despite greater poverty and discrimination, suggesting that poverty isn’t a sufficient explanation for criminality.

- He’d likely note that even within similar income brackets, disparities in crime rates persist, which he attributes to cultural differences rather than wealth itself.

Analyzing the Idea

If you divide crime rates by wealth, you’re essentially asking whether black Americans commit crimes at a lower rate than other groups when socioeconomic status is held constant. Here’s how that might play out:

- Poverty and Crime Correlation: Crime, especially violent crime, tends to correlate with poverty across all racial groups. Black Americans are disproportionately represented in lower income brackets—roughly 19% lived below the poverty line in 2022 (U.S. Census data), compared to 8% of non-Hispanic whites. If you adjust crime rates by income, the raw disparity (e.g., blacks committing over 50% of homicides despite being 13% of the population) might shrink because poverty amplifies crime risk universally.

- Within-Income-Group Disparities: Studies and crime data (like FBI Uniform Crime Reports) show that even when controlling for income, black crime rates often remain higher than those of other racial groups in the same economic bracket. For example, a 2011 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that among poor urban residents, black individuals still had higher homicide offending rates than whites or Hispanics. This suggests that wealth adjustment reduces, but doesn’t eliminate, the gap.

- Hypothetical Outcome: If you divided the homicide rate by, say, the poverty rate for each group:

- Black poverty rate: ~19%, homicide rate: ~50% of U.S. total (for 13% of population).

- White poverty rate: ~8%, homicide rate: ~30% of U.S. total (for 60% of population).Normalizing might show black crime rates per poor person are still higher than white rates per poor person, though the gap narrows. Exact numbers depend on the dataset and methodology, but the pattern holds in most analyses.

- Limitations: Wealth doesn’t capture all socioeconomic factors (e.g., education, family structure, neighborhood effects). Sowell would argue that single-parent households—more prevalent among black families (around 64% of black children born to unmarried mothers vs. 24% for whites, per CDC data)—correlate strongly with crime independent of income. Adjusting for wealth alone might obscure these variables.

Does It "Prove" Less Criminality?

- No Definitive Proof: Adjusting for wealth might lower the relative crime rate for black Americans compared to unadjusted stats, potentially aligning it closer to other groups. But "less criminal" implies a reversal of the trend, which data doesn’t typically support—disparities persist even after such adjustments.

- Interpretation Matters: Advocates might argue it "proves" systemic factors like poverty drive crime more than race, aligning with narratives Sowell critiques. Sowell, however, would counter that this overlooks agency, culture, and historical shifts (e.g., rising crime post-1960s despite economic gains).

Conclusion

Dividing crime rates by wealth could suggest poverty plays a bigger role in black crime than raw stats imply, potentially reducing racial disparities in the numbers.

However, it wouldn’t "prove" black Americans are less criminal than others—it would just reframe the question.

Sowell’s view would likely be that such an exercise misses the deeper cultural and behavioral drivers he emphasizes, and the data, even adjusted, wouldn’t fully support a narrative of equal or lower criminality across groups.

For a precise answer, you’d need to run the numbers with current datasets, but the broad patterns suggest adjustment narrows, rather than reverses, the gap.

@Grok

Yet another thread where left wing deviants demonstrate their own racism and highlight the differences between real liberals and lunatic doper burb brats and their brainwashing.

Black cultural failures are endemic, and this has been known for a long time now, as many genuine liberals like Patrick Moynihan have been studying and pointing out since the 1950's. The difference is real liberals will take unpleasant real life facts and try to actually do something to reverse them, while commies work hard to make sure their failures and degeneracy get a lot worse, so they can then manipulate minorities into committing a lot more violence and trash their own neighborhoods and kill their own children in ever increasing numbers.

Anybody actually serious about Civil Rights and what the real problems were will get a copy of Hugh David Graham's book The Civil Rights Era, a detailed critique of how and why so many programs went wrong and resulted in worsening the problem instead of helping improve them. Short answer is the real liberals let the radicals take over the agenda, the same type of butt stupid racist sociopaths that post here sniveling about TRump 24/7.

Black cultural failures are endemic, and this has been known for a long time now, as many genuine liberals like Patrick Moynihan have been studying and pointing out since the 1950's. The difference is real liberals will take unpleasant real life facts and try to actually do something to reverse them, while commies work hard to make sure their failures and degeneracy get a lot worse, so they can then manipulate minorities into committing a lot more violence and trash their own neighborhoods and kill their own children in ever increasing numbers.

Anybody actually serious about Civil Rights and what the real problems were will get a copy of Hugh David Graham's book The Civil Rights Era, a detailed critique of how and why so many programs went wrong and resulted in worsening the problem instead of helping improve them. Short answer is the real liberals let the radicals take over the agenda, the same type of butt stupid racist sociopaths that post here sniveling about TRump 24/7.

Last edited:

Always comical how all these Red Hat Club racists are so afraid that some kid in a hoodie is going to walk down the street of their gated community someday

Are they?

Got any examples you can share, Anchovies?

You might want to check with Bowel, Phan, Jew-no, or Douche.No, I don't.

You might want to check with Bowel, Phan, Jew-no, or Douche.

No, I don't.

volsrocks

Verified User

LinkThat's not what you said the other day, eh?

So tell us, how does demagoguing crime statistics profiled by race without context address address the situation?Yet another thread where left wing deviants demonstrate their own racism and highlight the differences between real liberals and lunatic doper burb brats and their brainwashing.

Black cultural failures are endemic, and this has been known for a long time now, as many genuine liberals like Patrick Moynihan have been studying and pointing out since the 1950's. Te differences is real liberals will take unpleasant real life facts and try to actually do something to reverse them, while commies work hard to make sure their failures and degeneracy get a lot worse, so they can then manipulate minorities into committing a lot more violence and trash their own neighborhoods and kill their own children in ever increasing numbers.

volsrocks

Verified User

Appalachia is the poorest part in America.... And 98% White.... The violent crime rate nowhere near matches the blacksDivide the crime rate by wealth and you get a different slant. The poor commit crimes to survive. The wealthy loot because they can.

Welfare State Expansion and Family Breakdown

2. The "War on Poverty" and Economic Dependency

3. Criminal Justice Policies and Soft-on-Crime Approaches

4. Education Policy Failures

5. Housing and Urban Policies

@Grok

- Policy Context: The Great Society programs under President Lyndon Johnson, starting in the 1960s, expanded welfare benefits like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, later TANF). These programs often provided more support to single mothers, with eligibility tied to income and household status.

- Impact on Black Families: This created a disincentive for marriage and two-parent households. Before the 1960s, most black children (around 75%) were raised in two-parent families, despite poverty and racism. By the 1990s, this dropped to about 33%, with over 60% of black children born to unmarried mothers (CDC data). Critics, including Sowell, link this to welfare rules that penalized married couples by reducing benefits, undermining family stability.

- Link to Poverty and Crime: Single-parent homes correlate strongly with poverty. Black single-mother households had a poverty rate of 35% in 2022 (U.S. Census), vs. 5% for black married couples. Studies also show children from fatherless homes are more likely to engage in crime, with the doubling of black homicide rates post-1960s as evidence of this trend’s downstream effects.

2. The "War on Poverty" and Economic Dependency

- Policy Context: Democrat-led initiatives like the War on Poverty aimed to reduce economic hardship but expanded government assistance programs, including food stamps, housing subsidies, and Medicaid. These programs fostered dependency rather than self-reliance, discouraging work and entrepreneurship. Black labor force participation was higher in the 1940s (e.g., 87% for black males in 1940 vs. 67% by 2010, per BLS data) when fewer such programs existed, despite worse economic conditions.

- Poverty Outcomes: While poverty rates fell initially (from 55% for blacks in 1960 to 32% by 1970), progress stalled, hovering around 19-22% since the 1990s (Census data). This reflects a culture of entitlement over achievement, exacerbated by policies that didn’t prioritize education or job creation over handouts.

- Anti-social Trends: Reduced economic agency is linked to idleness, which can be tied to higher crime rates, especially among young black males with lower employment prospects.

3. Criminal Justice Policies and Soft-on-Crime Approaches

- Policy Context: Democrats have often pushed for lenient sentencing, bail reform, and reduced incarceration, especially since the 1990s (e.g., the 1994 Crime Bill had Democrat support but later criticism from the party shifted toward reform). Recent examples include progressive DAs in cities like Philadelphia and San Francisco, backed by Democrat leaders, adopting non-prosecution policies for certain crimes.

- Impact on Crime: This emboldens criminal behavior by reducing deterrence. For instance, after bail reform in New York (2020), recidivism rates rose, with 17% of released defendants re-arrested within 60 days (NYPD data). In black communities, where violent crime is concentrated (e.g., 53% of U.S. homicides in 2021 per FBI stats), this can perpetuate a cycle of victimization and lawlessness. Excusing crime as a response to poverty or racism—common in Democrat rhetoric—undermines personal responsibility, a key factor that curbs anti-social behavior.

4. Education Policy Failures

- Policy Context: Democrats have historically supported teachers’ unions and opposed school choice (e.g., vouchers or charters), prioritizing public school funding over competition. In urban areas with large black populations, this has locked students into failing systems.

- Impact: Black students in cities like Washington, D.C., or Detroit often attend schools where proficiency rates in math and reading are below 20% (NAEP data). Contrast this with charter schools, where black students outperform peers (e.g., Success Academy in NYC), but Democrat resistance to choice limits access.

- Link to Poverty and Crime: Poor education reduces economic mobility. Black high school dropouts have a poverty rate of 30% vs. 10% for graduates (Census)—and increases crime risk, with studies showing dropouts are 3-5 times more likely to be arrested (Bureau of Justice Statistics).

5. Housing and Urban Policies

- Policy Context: Democrat-led public housing projects and rent controls, prominent since the New Deal and expanded in the 20th century, aimed to aid the poor but often concentrated poverty in urban ghettos.

- Impact: These policies trapped black families in high-crime, low-opportunity areas. For example, Chicago’s Cabrini-Green became synonymous with violence,

@Grok