He's insane.I do not know what the hell deaf studies is.

IMO, it's irrational to try to rationalize irrational behavior.

He's insane.I do not know what the hell deaf studies is.

Are you sure?

Yes. Many switched Parties or voted for the Unionist parties. Grant was a War Democrat who switched Parties, by the way.

Is that right?

Certainly not Democrat.

fcfreepresspa.com

fcfreepresspa.com

Is that right?

Who told you that?

Talking to yourself again?

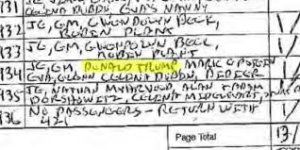

You voted for him.Guess who this guy voted for?

Franklin County Drag Queen Sentenced on Child Porn Charges from Last Year

A man from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, who was accused last year of uploading numerous sexually explicit child pornography films to Dropbox, has been sentenced this month. Brice Williams, as reported by […]fcfreepresspa.com

Same people as you voted for.

The white nationalist Lincoln depended on the 100 northern War Democrats for support for his illegal war to impose a corporate welfare state.

No, I'm addressing Y O U.

Ulysses S. Grant was not initially a Democrat but rather a member of the Whig Party before the American Civil War. As the Whig Party dissolved, Grant, like many others, found himself politically adrift. However, he did not formally switch from being a Democrat to another party; instead, his political alignment evolved with the changing political landscape of the time.

Here's a brief outline of Grant's political journey:

- Pre-Civil War: Grant was a Whig, but by the time of the Civil War, the Whig Party had largely disintegrated. His sympathies during this period leaned towards the Union, which was more aligned with the emerging Republican Party's stance on preserving the Union.

- During the Civil War: Grant's role as a Union general made him a prominent figure, and his political views were seen as supportive of the Union cause, which was championed by the Republican Party.

- Post-Civil War: After the war, Grant became associated with the Republican Party. He was nominated for president by the Republicans in 1868 and won the election, serving two terms from 1869 to 1877. His administration is often credited with trying to protect the rights of freed slaves and implementing Reconstruction policies.

@Grok

Fake news. Grant was never a member of the Whig Party. Grant's father was a Democrat, and Ulysses was influenced by one of his father's best friends, John Aaron Rawlins, a War Democrat who gave an anti-slavery speech and sponsored Grant's military career and advancement. Grant expressed some agreement with some Whig platforms, but his rise was via War Democrats, and as already said many switched to the Republicans and also the National Union Party.

it depends on what church you go to.Yes, your ilk think all Christians are a threat. they oppose that kiddie grooming and sexual mutilation fetish Democrats and 'progressives' obsess over.

winterborn is a neocon toolbox who strongly believes in censorship and has ruined other boards with his bullshit.They did. Apparently, your eyes were tightly closed.

white lives do matter.